The Failure of the Aerotrain

It's fun to imagine riding the rails in the 1950s as a passenger in a crack train like the Broadway Limited or California Zephyr, sipping martinis and watching the scenery through panoramic windows, enjoying train travel in its prime. The truth is that the heyday of rail passenger service in America was before 1920 - not during the Fifties. In those times, railroads were profitable and passengers were happy.

Per capita rail passenger miles peaked in 1919 and fell by half during the Roaring '20s.

During the depression of the Thirties, the railroads struggled to stay alive. In the early 1930s, rail passenger ridership declined by 41% as a direct result of the economic depression. During that decade, various railroads introduced trendy, sleek streamlined trains to try and entice people to travel by rail. But, passengers and profits remained, for the most part, elusive. Rail traffic never reached pre-Depression levels until World War II began. During the depression of the Thirties, the railroads struggled to stay alive. In the early 1930s, rail passenger ridership declined by 41% as a direct result of the economic depression. During that decade, various railroads introduced trendy, sleek streamlined trains to try and entice people to travel by rail. But, passengers and profits remained, for the most part, elusive. Rail traffic never reached pre-Depression levels until World War II began.

In the early Forties, the railroads made money on passenger service only because of massive troop movements caused by World War II. But by then, trains were old and people were stuffed in them like sardines.

After the war, passenger business on the railroads dried up. Postwar per capita passenger miles dropped precipitously despite rapid economic growth. By 1949, they had fallen to 1929 levels. In the 1950s, train travel had become a mere shadow of its former self. People drove to their destinations. Or flew.

The Pennsylvania Railroad's experience was typical. Like the rest of the nation's railroads, the Pennsy had not earned a profit from passenger service since 1946, despite multi-million dollar investments in passenger equipment and facilities in the years following World War II. Competition from the use of automobiles for medium-distance intercity trips prevented the railroads from increasing fares enough to cover soaring labor and material costs.

Beginning in 1952, total passenger revenues began dropping significantly. In 1957, the PRR lost lost $57 million on its passenger operations. The railroads saw a possible solution in the development of a stylish, comfortable train which would combine light-weight, high-speed and low operating cost. They felt that such a train would draw people from their automobiles back to train travel. So, in the early 1950s, several railroads, including the Pennsylvania, approached General Motors Corporation, suggesting that GM develop a lightweight, high-speed passenger train that would combine low operating cost and high passenger capacity to help railroads turn a profit in the medium-distance (200-700 mile) market.

In 1955, General Motors proposed an answer: the Aerotrain. With air suspension and ultra-lightweight coaches, it was essentially a string of modified GM bus bodies on rails pulled by a 1,200 horsepower diesel engine.

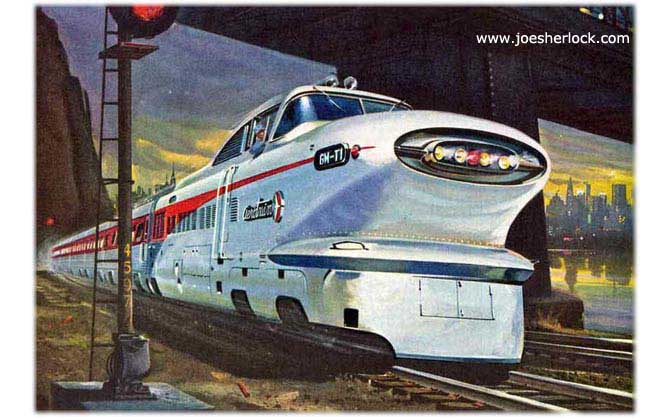

Styling was done by GM's Special Projects Studio and featured many GM automobile styling cues from the fifties, including multiple headlights, a wrap-around windshield, sweep-spear side trim in a contrasting color and an observation car/tail looking like the back end of a 1955 Chevy Nomad station wagon complete with wrap-around back window and prehensile fins.

Designer Chuck Jordan was responsible for the Aerotrain's unique look. He later designed GM Motorama dream cars, was instrumental in the design of the 1958 Corvette and headed the team that designed the 1959 Cadillac line. Jordan eventually became vice president of the General Motors Design.

Two prototype Aerotrains were made; each consisted of a single engine with ten passenger cars.

|

|

| At the 1956 Motorama, General Motors displayed a scale model of its new Aerotrain. |

The Pennsylvania Railroad leased the Aerotrain from General Motors and introduced it in February 1956. The train itself was very futuristic-looking and made everything else on the Pennsy look old fashioned. But the combination of extremely lightweight, short wheelbase coaches, single-axle trucks plus a bus-tuned air suspension caused the cars to 'almost beat the passengers to death' at anywhere near the designed top speed of 100 miles per hour. The railroad declined to buy any Aerotrains and turned the prototype back to GM after less than a year.

Each of the two prototype Aerotrains toured the country in an attempt to sell the concept to various other railroads.

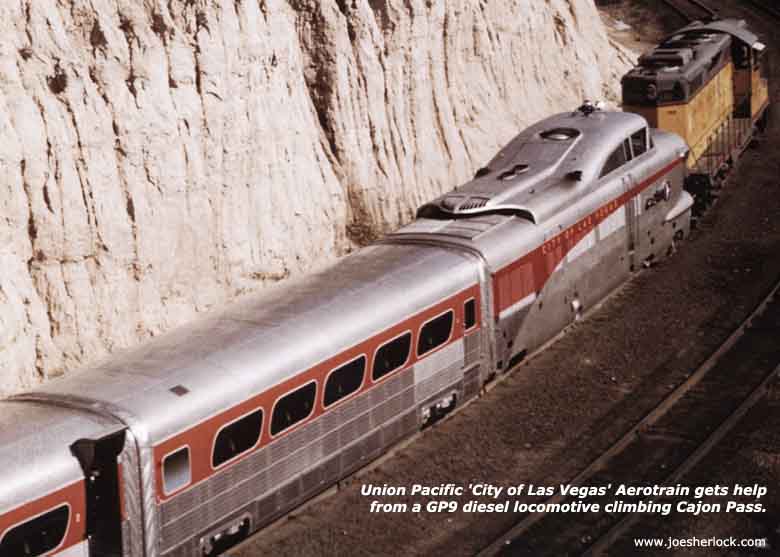

The Union Pacific tried it; service began in December 1956 from Los Angeles to Las Vegas. Fares were low - $17.99 round trip including free food onboard in the Chuckwagon Buffet car. The new service was much hyped - Liberace was in the engineer's seat when the inaugural run arrived at the Las Vegas station. But the Aerotrain was so underpowered that it required a helper diesel locomotive to climb Cajon Pass. And the Union Pacific experienced the same shortcomings as the PRR had noted.

The Union Pacific 'City of Las Vegas' Aerotrain was mildly popular but never carried a full passenger load. In September 1957, UP replaced the Aerotrain with a conventional passenger consist and returned the experimental train to General Motors.

The same shortcomings were reported everywhere - the train of the future rode like an old truck. The Aerotrain was a dismal failure - nobody wanted one. In 1957, both prototypes were finally sold at a heavily discounted price to the Rock Island Railroad for Chicago commuter service where slower operating speeds would hopefully produce a less-rough ride. Both Aerotrains were retired from service in 1966 - worn-out and unloved after only 10 years of service.

What happened here is a lesson for every business. The railroads clearly stated four needs: high style, comfort, light weight, low operating cost. GM only met three. They were so fixated on style and low cost, they forgot about comfort. They never tested the prototypes under real-world conditions. Ironically, getting fixated on style and cost-control at the expense of real-world conditions would continue to plague GM for years to come. (I'm thinking of the stylish-but-tippy Chevrolet Corvair of the early 1960s and the low-cost, dangerous X-cars - Chevrolet Citation, Pontiac Phoenix, Buick Skylark and Oldsmobile Omega - of the early 1980s. But those are other stories for another time.)

In any business, you must listen to the needs prospective customers. But you must also keep in touch with your customers during the development phase of a project to make sure that your offerings meet their needs under real-world conditions. That's true whether you're developing new trains, cars, software or services.

Test it before you sell it. Otherwise, you'll produce a flawed offering which will be doomed to fail.

A personal note: I have fond memories of riding on the Pennsy Aerotrain as a twelve-year old. My dad and I rode this train in the summer of 1956, departing North Philadelphia Station a little after 9:00 am and returning from a Pittsburgh round trip a little after 10:00 pm on the same day - on the same train. There was no dining car - box lunches were available - mine had a chicken sandwich with potato salad. There were also vending machines on board which dispensed candy and gum.

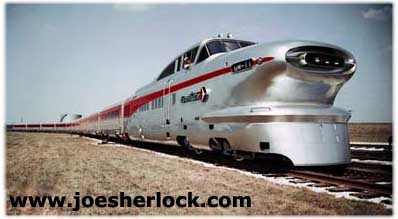

It was a very memorable trip - especially the ride around the PRR's legendary Horseshoe Curve. (The picture at the top of this page is from the Pennsylvania Railroad's 1956 calendar. The title of the painting is 'Dynamic Progress' by artist Grif Teller.) The train itself was very futuristic-looking and made everything else on the railroad look old fashioned - especially the turn-of-the-century station at North Philly. But the PRR wasn't as impressed with the train as I was.

More Aerotrain Facts: The Aerotrain was also tried by the New York Central and Union Pacific Railroads.

Aerotrain Locomotive No. 2 was eventually donated to the National Railroad Museum in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Set No. 1 is at the National Transportation Museum in Kirkwood, Missouri.

A scale replica of the Aerotrain carries sightseers along 30-inch gauge track at the Washington Park Zoo in Portland, Oregon.

Dubbed the 'Zooliner', it has operated there since 1959.

This 165 horsepower, diesel-powered streamliner transmits power to eight driving wheels through a hydraulic-type torque converter transmission. A governor holds the train to a 12-mile-per-hour maximum.

The Aerotrain was modeled in O-gauge (1:48 scale) and released by MTH Trains in late 2001. I have one - with Pennsylvania Raulroad markings - equipped with the Protosound feature which produces very realistic train sounds.

Having an Aerotrain running on my layout brings back memories of the trip my dad and I took many years ago. Sometimes when I see it, I can still taste that chicken sandwich.

To view a large photo of the Pennsy Aerotrain on my model train layout, click here.

Or, watch a 2.5 minute video of my O-gauge Aerotrain in action:

Other Pages Of Interest

copyright 2002-19 - Joseph M. Sherlock - All applicable rights reserved

Disclaimer

The facts presented on this website are based on my best guesses and my substantially faulty geezer memory. The opinions expressed herein are strictly those of the author and are protected by the U.S. Constitution. Probably.

Spelling, punctuation and syntax errors are cheerfully repaired when I find them; grudgingly fixed when you do.

If I have slandered any brands of automobiles, either expressly or inadvertently, they're most likely crap cars and deserve it. Automobile manufacturers should be aware that they always have the option of trying to change my mind by providing me with vehicles to test drive.

If I have slandered any people or corporations, either expressly or inadvertently, they should buy me strong drinks (and an expensive meal) and try to prove to me that they're not the jerks I've portrayed them to be. If you're buying, I'm willing to listen.

Don't be shy - try a bribe. It might help.

|